SUMMARY: Preliminary estimates of “prevent plant” acreage were released this week, with 3.41 million acres of the estimated total 7.71 million coming out of corn. We can all multiply USDA’s current yield estimate of 154.4 bushels times the revised acreage to get a reduction of approximately 480 million bushels. The real question is what impact that will have on price. The estimate from my corn forecasting model is $5.32 (range of $4.87-$5.76), compared to USDA’s current estimate of $4.80 (range of $4.40-$5.30).

I hope it is well documented by now that I find price forecasts only moderately useful for making hedging decisions. The primary reason is that price forecasting is based on future events, like weather, which are extremely difficult to quantify. However, there is a context in which I find the information helpful.

The markets reacted immediately to the new information, and price moved up quickly. The question I want answered is whether the reduced production will cause corn price to go up by $0.25, $2.50, or something in between. What I am really looking for is cases where the market appears to over react and creates buying or selling opportunities. Several marketing services have recommendations to sell the rally, and certainly that is appropriate if the market has over reacted. Alternatively, I want to avoid selling into a rally that is going to continue another $0.50, $1.00, or more.

Let there be no confusion. Creating a comprehensive econometric model to predict corn prices requires far more resources than I have at my disposal. At the same time, I get the impression that the media and many advisors either don’t understand basic supply and demand, or have a vested interest in making you believe that you can’t understand it. Perhaps the words are too harsh, but many of the statements which are made on the farm show programs and in print media simply indicate that the speakers do not have even a basic understanding of the difference between a demand curve and the quantity demanded at a price on that curve. The demand curve is relatively stable over short time periods, but quantity demanded can adjust very quickly to changes in price.

Let’s focus in on the recent release of PP acreage. First of all, demand is not a function of planted acres, so the demand curve would not be impacted directly. Demand is a function of population, income, price of related commodities, etc. The point being that the demand curve should be the same the day after the new acreage numbers that it was the day before. Therefore, making a new price projection should be as simple as sliding up or down the demand curve to reflect the increase or decrease in supply since the whole concept of supply and demand equilibrium is finding the point where consumers are willing to pay the price for a quantity that producers are willing to offer at that price.

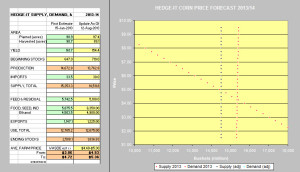

With that in mind, I set out to derive a demand curve that I could use as a basis for estimating the impact of changes in supply. The format of the WASDE report pulls together the key elements of supply and demand which are most talked about in the media, and is a format that we are all familiar with.  The attached figure has a table containing two columns of data, “First Estimate” and “Updated As Of.” The First Estimate is a projection made early in the year before the first crop reports were released, so it is based strictly on trends and estimated projections. The right side of the figure is a chart with the projected supply and demand curves.

The attached figure has a table containing two columns of data, “First Estimate” and “Updated As Of.” The First Estimate is a projection made early in the year before the first crop reports were released, so it is based strictly on trends and estimated projections. The right side of the figure is a chart with the projected supply and demand curves.

You can see from the first column that the projected planted acres turned out to be high, leading to harvested acres being too high. Likewise, yield was estimated too high as well. But these numbers are a glimpse at what might have been if normal weather patterns had developed. The projected price was $4.29 (range $3.86-$4.72). This was a clear signal that if normal weather developed, it would take some very creative and aggressive marketing to cover costs and generate desired profits.

The beauty of the model is that USDA numbers or other estimates can be entered easily and new price estimates obtained immediately. The second column reflects the numbers released in the August 12 report with estimated price range of $4.40-$5.30. Immediately below the WASDE estimate is the model’s projection of $4.53-$5.36. In the chart to the right, you can see the original supply and demand estimates from the early projections, and the adjusted supply based on USDA numbers. It should be noted that the model is projecting a price slightly higher than the USDA projection, but keep in mind that the price projection is only meant to be used as a reference point.

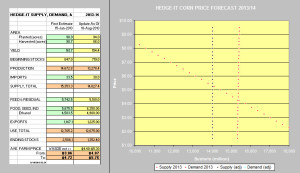

The second figure is identical to the first with one change. The planted acres have been reduced by 3.4 million acres. Using USDA’s estimate for percent of acres harvested and yield, that lowers harvested acres to 86.0 million acres and production to 13.278 billion bushels. The resulting price projection is $5.32 (range $4.87-$5.76), or an increase of $0.38 per bushel. As of Friday’s close, the market has only rallied $0.15-$0.16 off Tuesday’s close before the new information was released. My interpretation is that we could expect some more movement to the up side, but this information is not what gets us back to $6.00 or more.

Street estimates for yield are all over the place, from 4-5 bushels higher to 4-5 bushels lower. Again, the question is what impact a revision in yield estimates would have on price. Lowering the yield to 150 bushels with the acreage used above still only gets to a projected price of $5.61 (range $5.14-$6.08). There are many other combinations of “what if” that could be tested with the model, but I think it is clear that if there isn’t an unlikely shift in demand or additional revision of acreage or yield, the futures market may struggle to get above $5.50 for Dec corn. This would be an excellent time to have settled on a trend indicator that would signal if the downward trend was changing.

Finally, a word of caution. It is possible that there could be a sudden shift in demand tomorrow, next week, or some time in the future that would alter all of these projections. For example, if all exports were stopped for internal or external reasons, or ethanol production was outlawed, it would shift the demand curve. Just be aware that the external factors that would move the demand curve are not factors like heat units, rainfall, and frost threat. Those are factors that will impact production and account for roughly 95 percent of supply. Supply will be the dominant force in moving the price in the short run.

To summarize, the forecasting model was developed as another tool to assist in trying to interpret the impact of data that is being generated by USDA or by private researchers. The model is a watered down version of what would be required as a comprehensive econometric model to explain many of the complex relationships for corn supply and demand. However, it does bring into focus the fact that demand does not change significantly with each new announcement about factors which impact supply. Sliding up and down a demand curve gives good estimates for the short run impact of selected supply changes. It is an excellent tool for identifying a base reference point and short term changes around that reference point. Don’t let the media and marketing advisors convince you that price anticipation is rocket science.

As always, comments and questions are welcome and encouraged.

Posted on 18 August 2013 by Keith D. Rogers